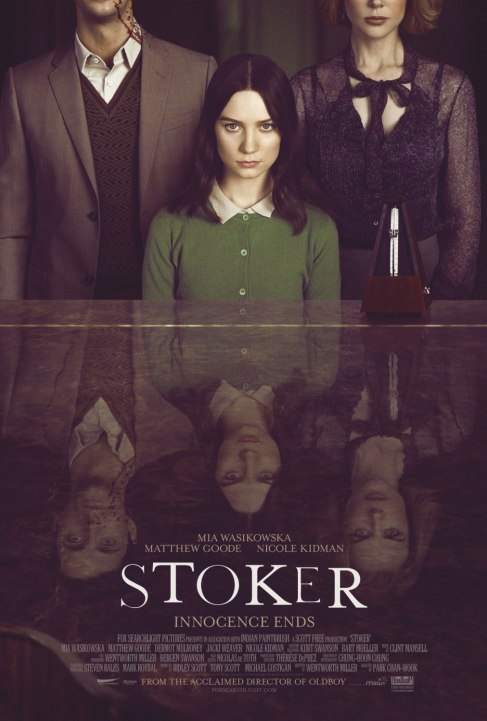

It’s fascinating to me how often boring films are still hailed as great for their aesthetics when they are directed by an asian filmmaker. I saw Stoker this weekend and while I heard good things from my crowd of English speaking indie film-lovers, the film itself wasn’t very good. Afterward I realized that the compliments I had heard focused mainly on the cinematic style and the approach of the director, Park Chan-wook, but not the drab content. While it’s certainly true that some directors are better at visual storytelling, and providing aesthetic experiences on film (Sofia Coppola, Ang Lee, etc.) it’s seems that when my crowd (which I generalize across the population) critique Asian film-makers we often focus solely on this aesthetics and ignore questions of plot or narrative that would normally be paramount. Perhaps this is a hold over from seeing Asian language films where the royal we focus on aesthetics for lack of language fluency, or perhaps it’s a product of our liberal fawning for multi-culturalism. I saw a similar scenario when teaching writing to ESL students who wanted to express themselves in nuanced ways but lacked fluency and so found that the standards were lowered by their professors for content so long as they worked hard and produced well structured well researched papers. In that scenario I think the altered standards made sense but for film projects its unjustified. Directors can choose any script they like and have it translated if need be, so why would we excuse their choosing poor material? Perhaps what this really reflects is how deeply verbal language is ingrained in our western culture. Perhaps our cultural expectations for film are different? Perhaps, perhaps… either way I’m paying more attention to the recommendations I get from friends. If they say a film is beautiful Iwant to know why.

The manor houses, the accents, the rigid hierarchies- All these things we consider ‘english’ in the U.S. are included in Downton Abbey and for old time mystery readers like me it’s a lot of fun but why is so popular right now- and why with so many people? I wonder if we can’t look back to Upstairs Downstairs- and even further to Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead and see that the english manor life is generally a fascination for people in times of social change and economic uncertainty. Perhaps what we love about Downton is the depiction of emerging class consciousness- something that echoes our own experience today but in a less visceral manner because it is historically removed.

Skyfall is an awesome movie- the stunts, the plotline, and the character arcs are super fun for a fifty year old franchise. But most interesting is how ably it illustrates what I call ‘Techno-Masculism’- the presumptive gender associations between technology and masculinity. In the opening sequence alone- Bond demonstrates his ability with firearms, speeding cars, moving trains and a giant crane that he uses variously as a shield, a weapon and a bridge that allows him to pursue his enemy across uncoupled train cars.

His boss M however is portrayed as inept at technology, with a room full of male aids who translate her orders into techno-speak, all in the pursuit of a digital file that she (personally somehow) has lost to the enemy. M’s physical representative on the scene is another woman, Moneypenny, who is later chided by Bond and others for following her orders from M, particularly an order to fire a tricky shot which hits Bond. There again M is a failure for not following protocol better and Moneypenny is a poor agent because she does follow protocol and orders. Bond, on the other hand is the reckless agent who put himself in harms way, yet, it is Moneypenny who takes the blame for Bond’s death and ultimately winds up behind a desk as the secretary to the man who replaces M.

Examples in the film are manifest and a content analysis could count them, but this discourse analysis also lends itself to the genre of action films overall and to the nascent film work covering the rise of new media.

I saw the acclaimed twisty thriller Side Effects this weekend and it was all the more a reminder of how central social and natural sciences are to the mystery genre. This film features an actual psychologist trying to work through the web of scientific evidence (social and natural) that leads to the climax, but it’s little different from those sleuths of old. Of course Arthur Conan Doyle set out to debunk mysticism with the empirical Holmes, but Doyke was far from the most influential mystery writer. Agatha Christie’s Poirot and Miss Marple employed social science methods- Psychology, Sociology, Anthropology and even Communication theory in order to solve their crimes and in the process these controversial academic subjects became entrenched parts of the popular culture in the mid to late twentieth century. Now it seems we’re back to hard science with CSI and Elementary but the point remains that the work of women like Christie, Sayers and Heyer- whose combined book sales are greater than the bible or Shakespeare were fundamental in an important aspect of western cultural development and have also been fundamentally ignored.

Facts of Life was a foundational moment in television history. After years of comedies

featuring female leads- I Love Lucy, Mary Tyler Moore, Mama’s Family, Maude, it was Facts of Life that finally introduced the panel of four archetypal characters- the practical realist (Jo), the brazenly confident beauty (Blaire), the quirky disaster (Tootie), and the frumpy comic (Natalie) that has become standard on subsequent shows like the Golden Girls, Sex In The City and Girls. Are we witnessing the establishment of a stock character rotation like that of the Comedia Del Arte tradition? If so it’s interesting to note that across the four shows mentioned above each represents a different generation of women- and does so consciously. It is also interesting how the ethnic diversity of the group has shifted over time- FOL featured one African American, one Polish working class girl, one Jewish girl, and one wasp. That diversity has slowly eroded so that we have a very white, very upper middle class panel on Girls.

All the readings this week on Content Analysis dealt with the issue of latent/manifest content. This debate struck me largely because it lies at the core of my own distinction between what I can view quantitatively and what I cannot. In a film that features multiple discourses and therefore symbols with potentially varied meanings, the difficulty for performing a content analysis rests on whether or not one can reasonably associate theoretical or symbolic meaning to distinct events, words, or actions captured on film. Berelson provides a loose notion of a spectrum with deference to the complexity of interpreting a shared meaning whereas Thomas reduces the process to a matter of semantic agreement between the researcher and the reader of the study. I think Steppel is most clear about the expectations of a good content analysis despite spending the least time discussing manifest/latent content. His argument limits the range of manifest content to that which can be justified through existing scholarship- and that is probably best. For myself though, it will be a challenge to make those connections clear enough to justify some of the units of analysis that I hope to include.

Today’s my first video game theory class.

Welcome to WordPress.com! This is your very first post. Click the Edit link to modify or delete it, or start a new post. If you like, use this post to tell readers why you started this blog and what you plan to do with it.

Happy blogging!